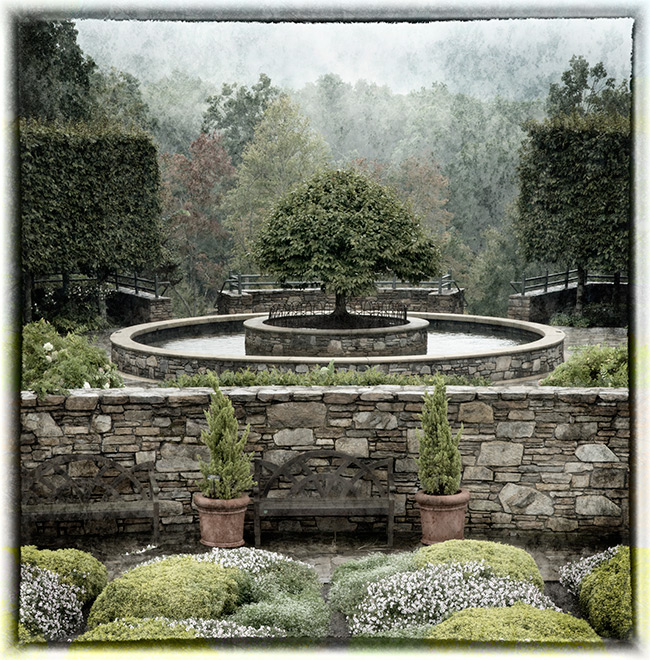

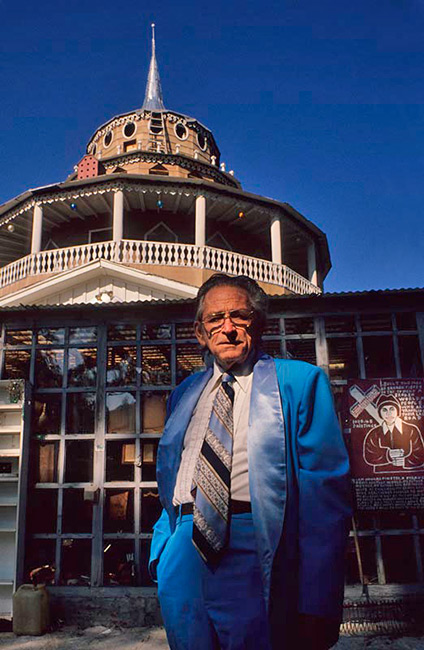

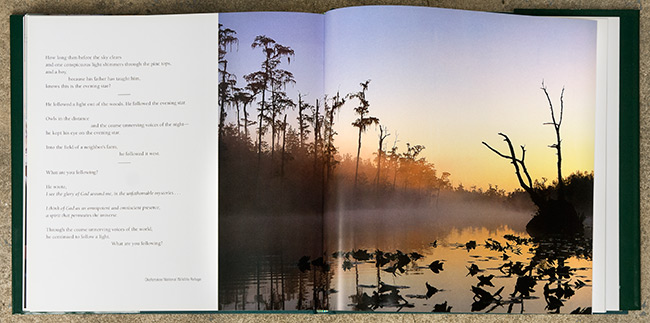

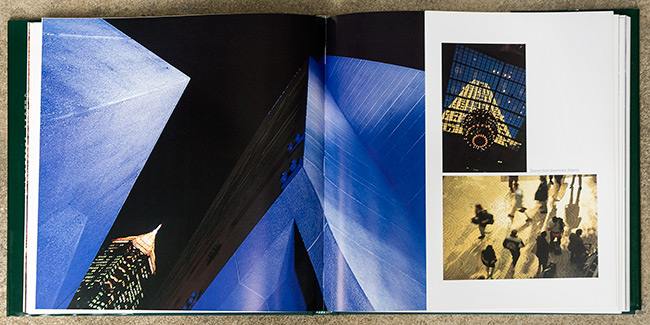

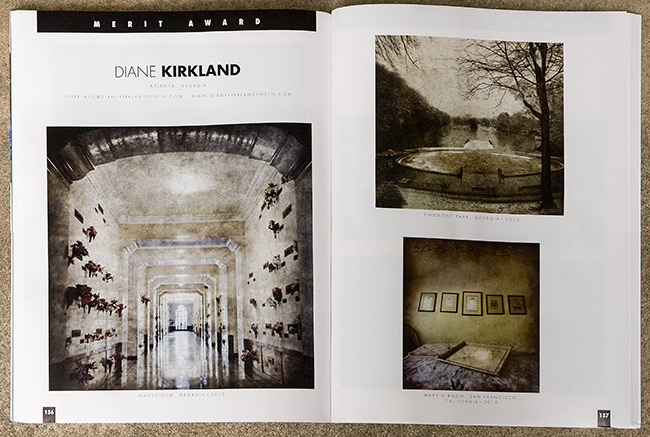

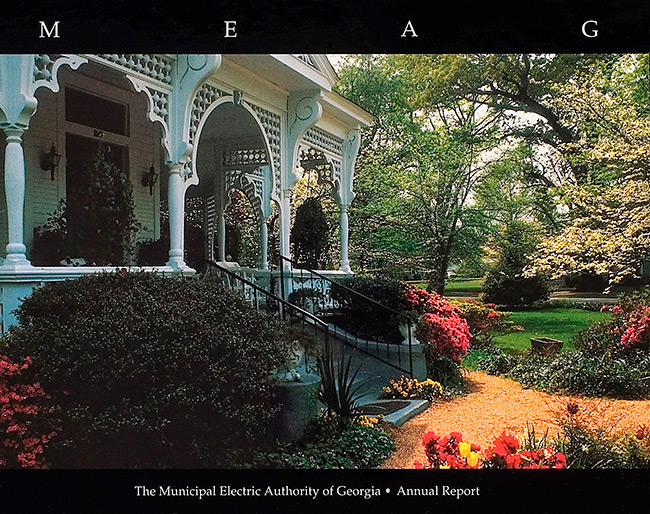

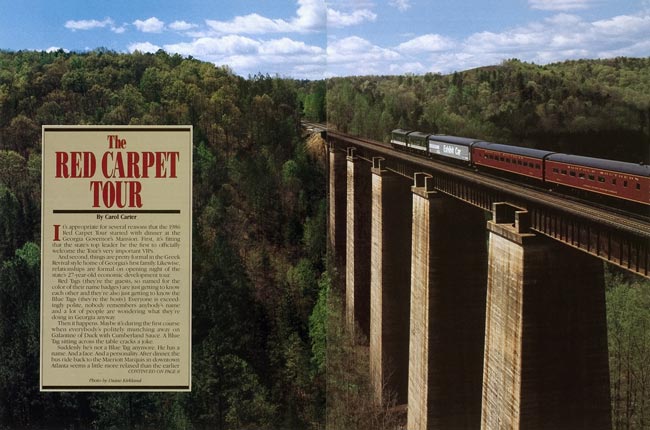

In her role as the senior photographer with Georgia Department of Economic Development for twenty five years, Diane Kirkland gained valuable experience in handling photography for advertising campaigns, publications and websites. She is skilled in relating to the travel industry as well as the manufacturing and industrial sector to create unique images that will make your advertising distinctive.Her work has appeared in national and international publications, including the New York Times, Time Magazine, USA Today, Southern Living, and the Times of London.

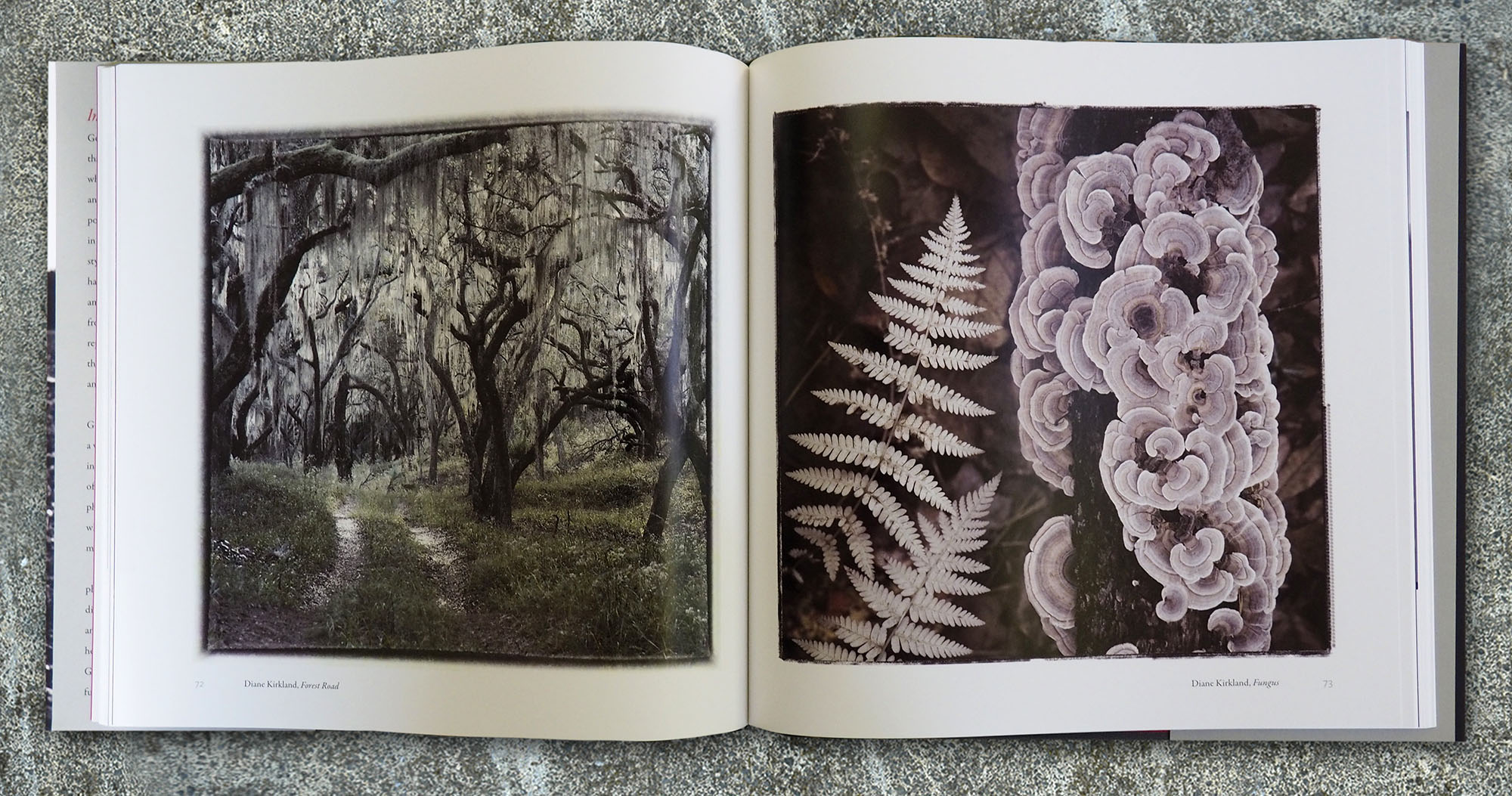

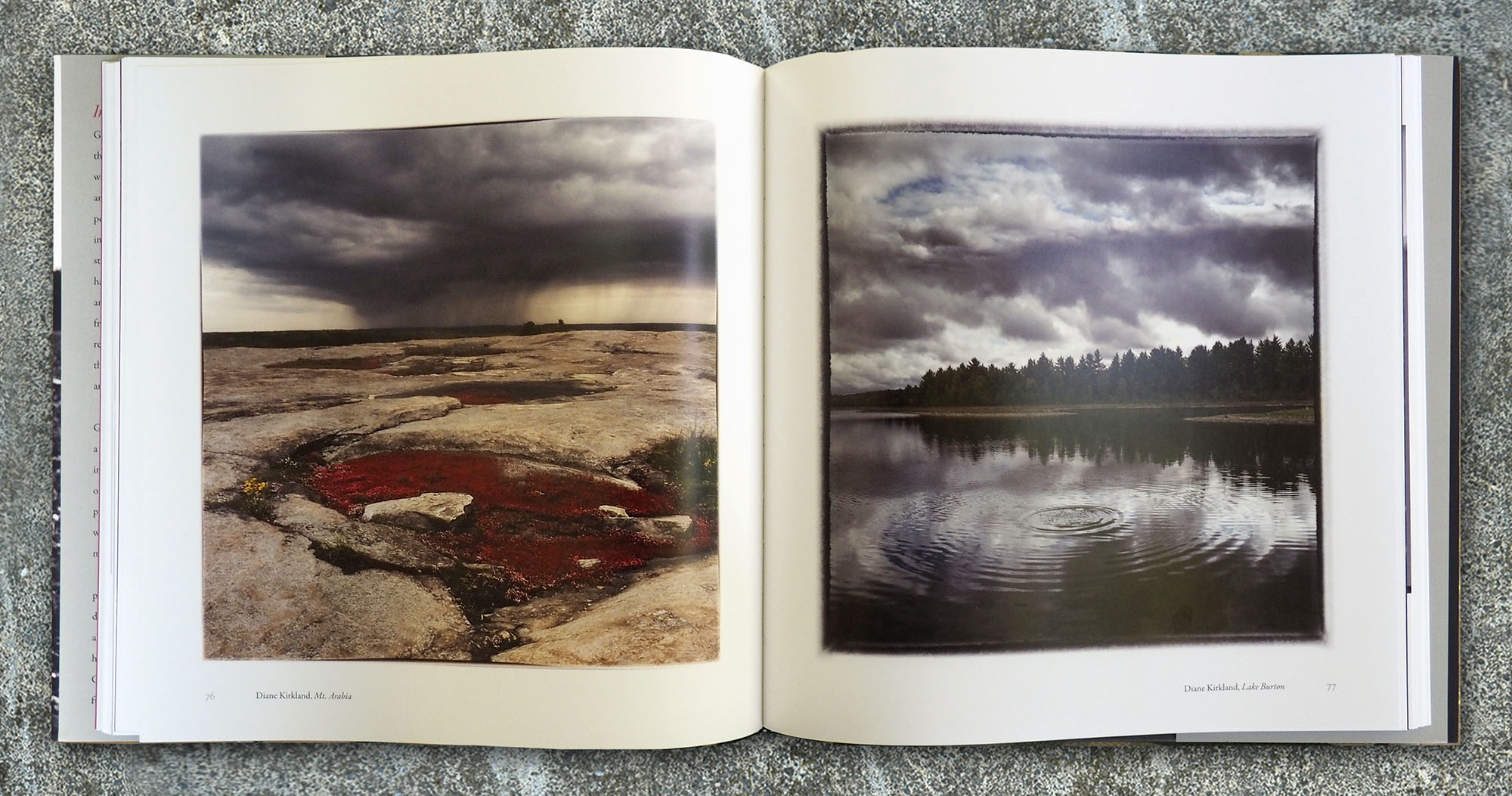

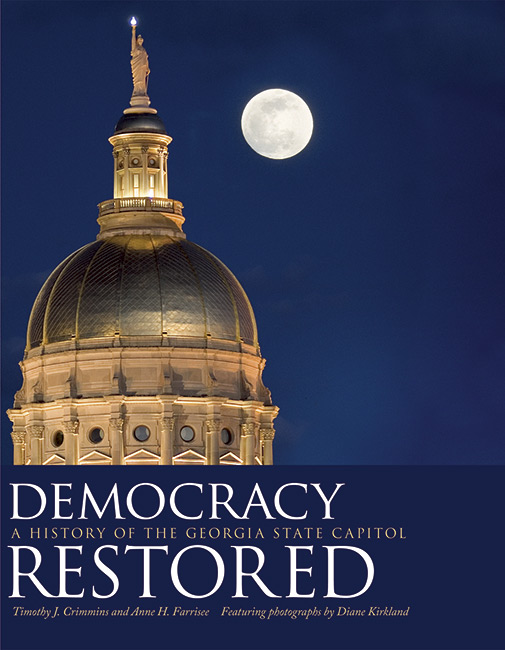

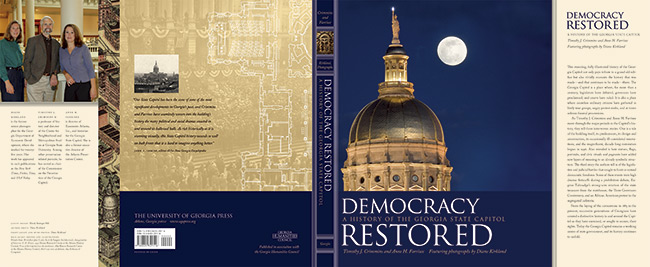

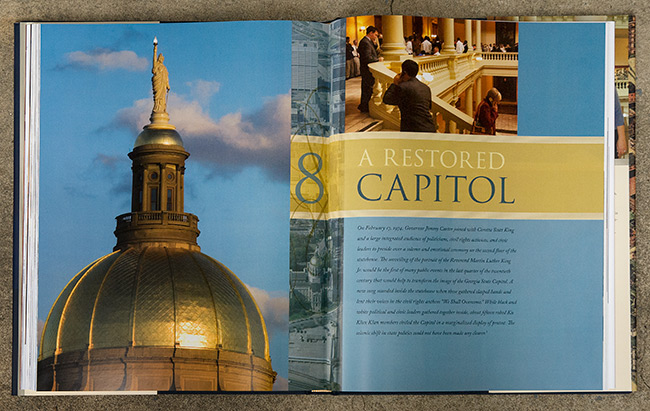

Diane is the exclusive photographer for Oglethorpe’s Dream, A Picture of Georgia (2001), a photographic book depicting the beauty and cultural traditions of Georgia, and the book Democracy Restored, A History of the Georgia State Capitol (2007).

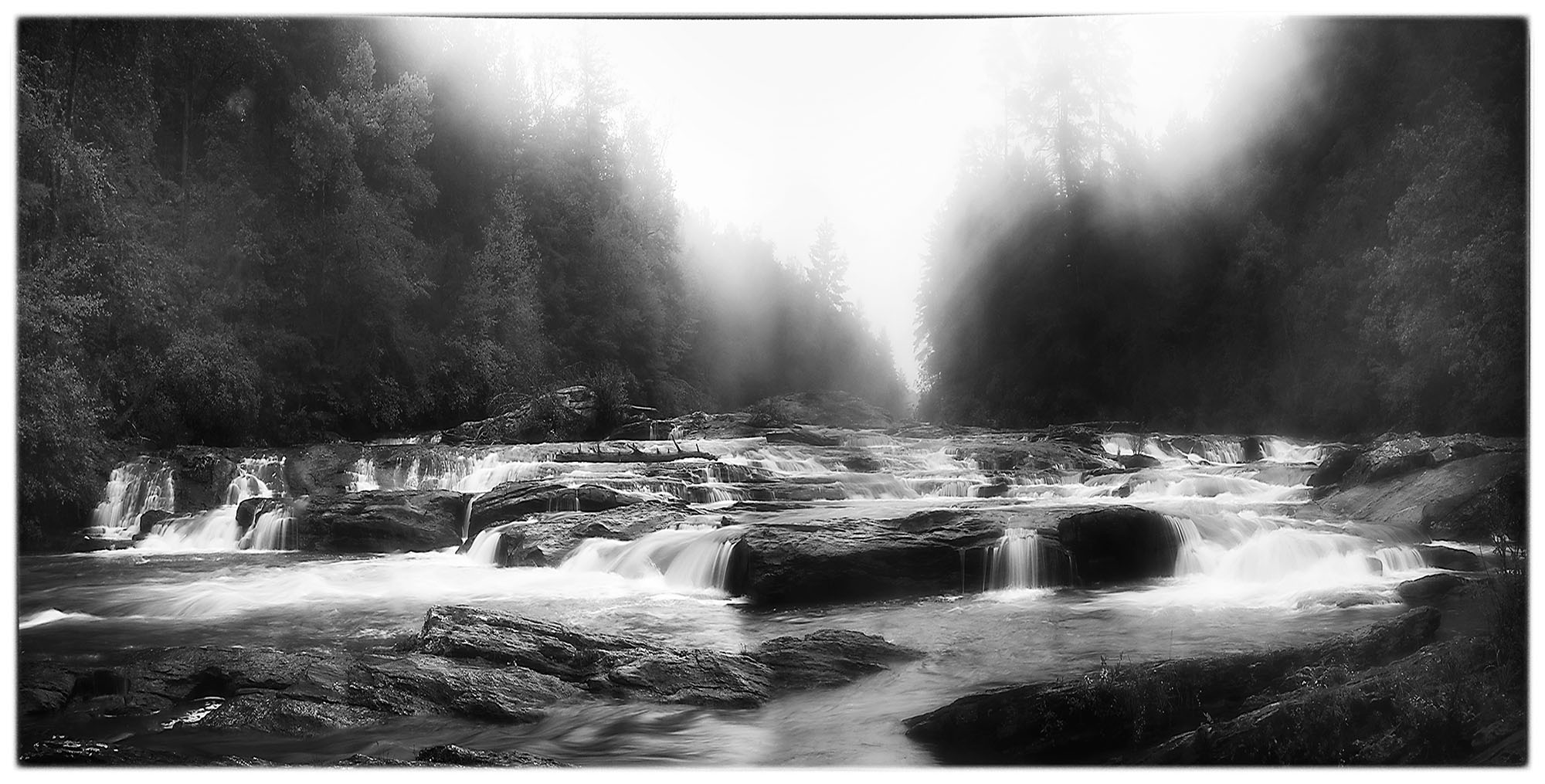

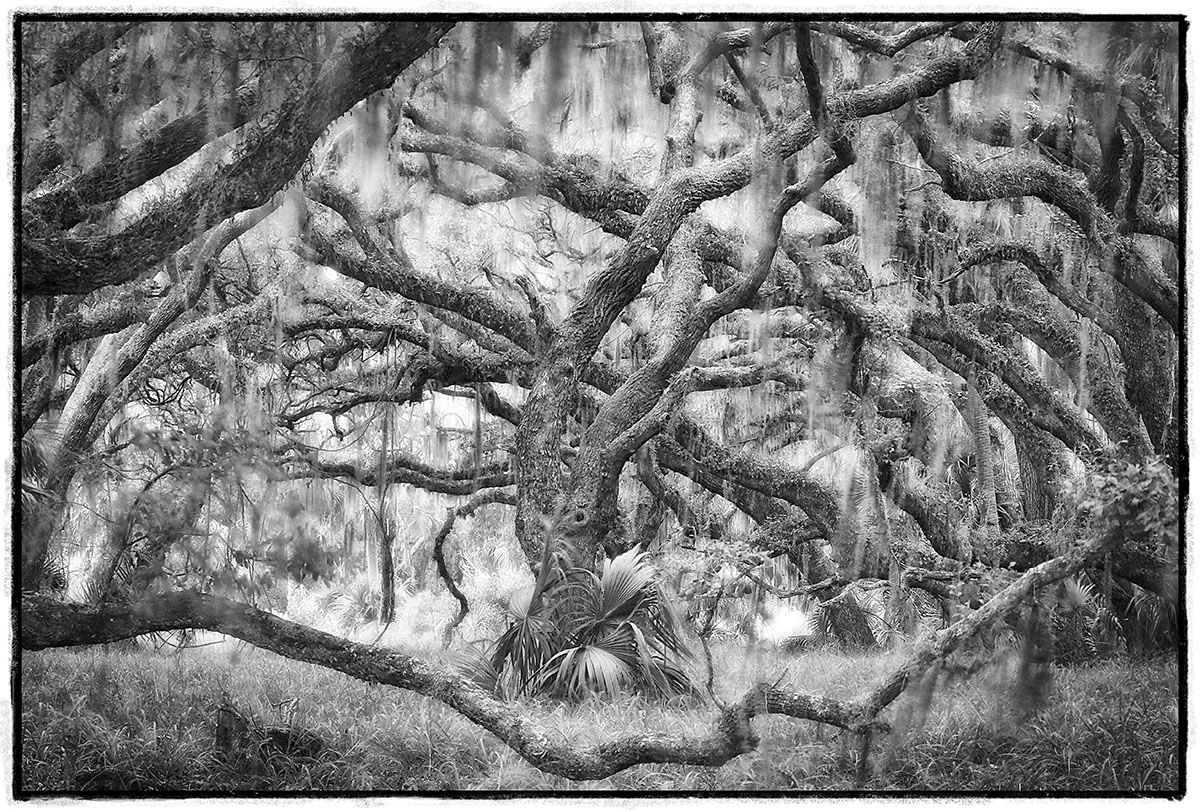

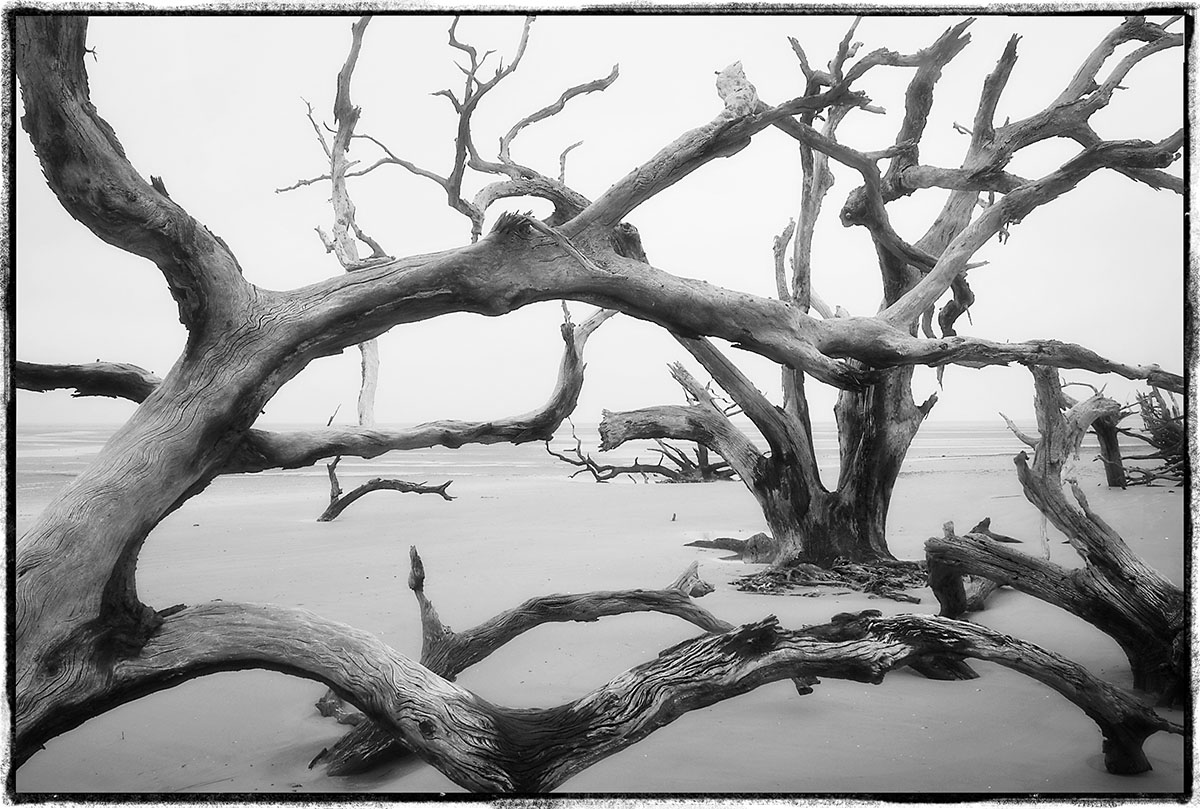

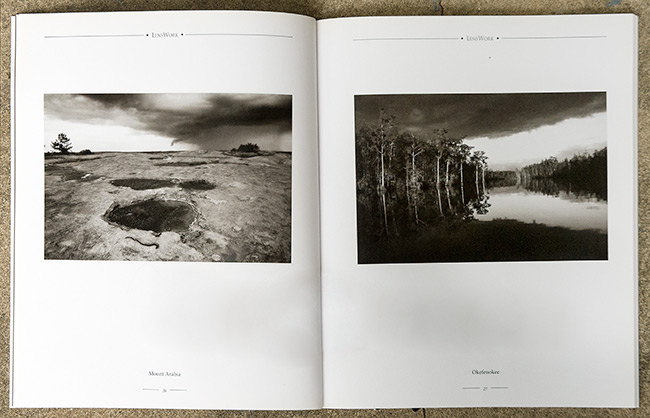

Also, the international publication Lenswork Magazine featured 18 of her black and white natural landscapes of Georgia.The Georgia Council for the Arts selected Diane to join their 2008-2010 Touring Artist Rosters and she was also invited to join the Southern Arts Federation. which is a multi-media artist registry that spotlights outstanding artists who live and work in the South.

In addition, Diane is the recipient of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources 2007-2008 Artist in Residence Grant.

Call or email Diane now and make your promotions reverberate.

Diane Kirkland Photography

1075 Hudson Drive NE

Atlanta, GA 30306

(404) 872-7761

dkirkland@dianekirklandphoto.com

Macroworld

Click to scroll down to Fungi, Lichen, Moss, or Slime mold photos.

Fungi

Fungi are everywhere and only an estimated 5% have even been identified. They outnumber plants by a ratio of 6 to 1 and the largest single organism on Earth is a fungus living in Oregon that covers 2,200 acres and weighs over 6,000 tons. Along with slime molds and bacteria, fungi help decompose decaying matter into a rich soil and it then feeds the nutrients to the roots of plants with tiny underground filaments. Plants could not survive or share nutrients without the help of fungi.

Researchers are only now beginning to recognize the amazing qualities of fungi. It shows great promise for numerous medical applications, such as boosting our immune system, preventing, and treating cancer and remediating depression. Fungi are being used to decompose all sorts of nasty pollutants such as petroleum spills and even radioactive particles. They are not picky eaters and any carbon-based product is food for fungi. They also show great promise as a natural form of pesticide, biofuel and as a decomposable packing material substitute for Styrofoam.

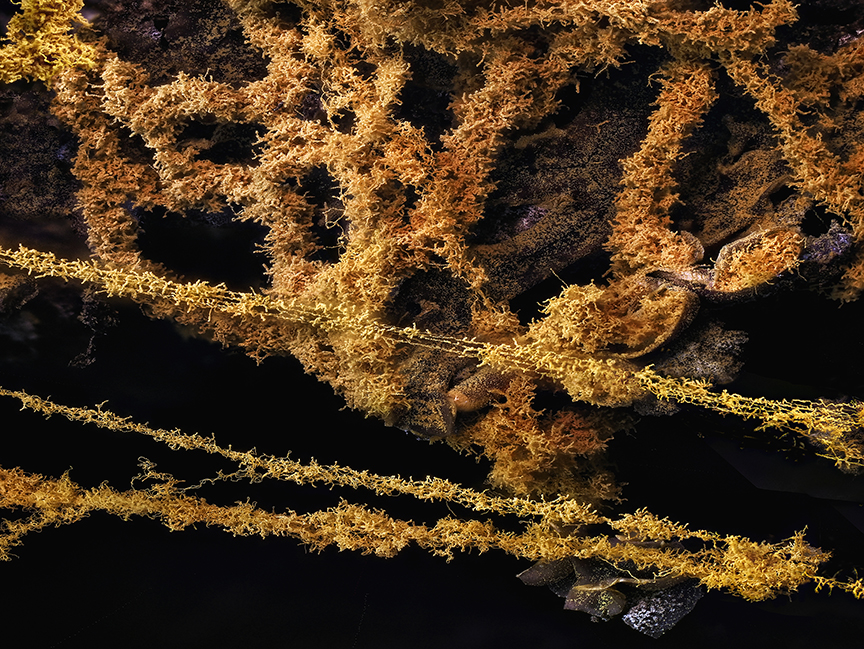

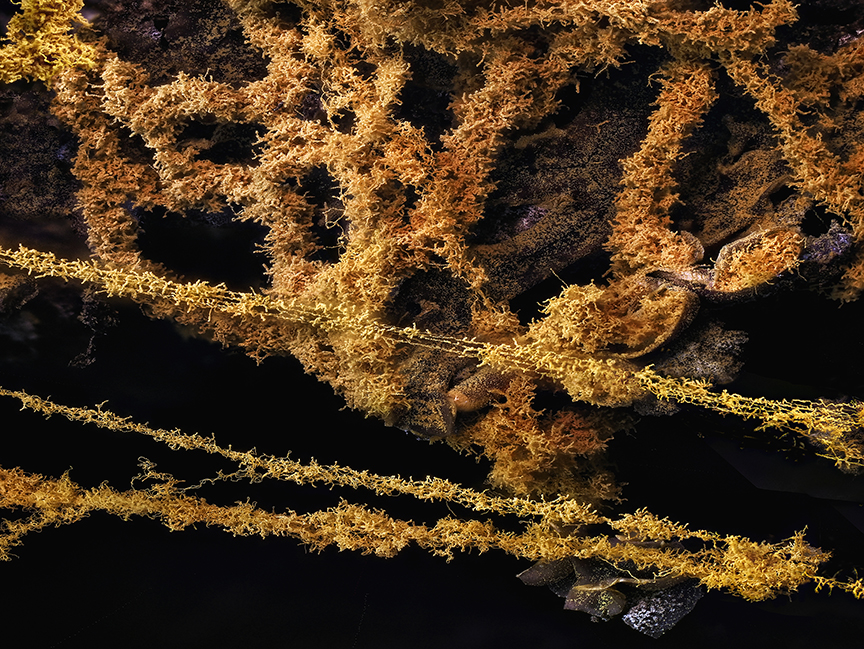

Lichen

Lichen are a combination of two or sometimes three separate organisms: a fungi, an alga, and occasionally a cyanobacteria. Since the fungus cannot produce its own food, it feeds off the photosynthesized sugars produced by the algae. In return, the fungus helps the algae spread its territory from being water bound to land dwelling. This partnership is known as a symbiotic relationship. When the lichen is dark green, brown, or black, it is an indication that cyanobacteria is also present. Cyanobacteria is useful for “fixing” nitrogen in the air or soil into a form that the lichen (and plants) can absorb. Lichens need clean fresh air and water to survive so they are good indicators of pollution. Only a few hardy lichens can survive in our cities because of pollution from highways and factories.

There are three basic shapes of lichen which are determined by the type of fungus combined with the algae: foliose which are leafy like lettuce; fruticose which can be branching cup shaped or stringy beard-like; and crustose (crusty) lichens that form a tight paint-like bond in bright colors of yellow, orange, red, gray, or green. These crusty lichens can grow on everything from street signs, tombstones, rocks, and trees.

Moss

Mosses were the very first in the plant kingdom to emerge from the water and survive on land, resulting in a unique system of reproduction to cope with dry conditions. Mosses can vary between sexual and asexual reproduction depending on how crowded their colony has become. In asexual reproduction, known as fragmentation, a section of the moss breaks off and becomes a new plant. If the moss colony becomes too crowded, the moss plant produces separate male and female cells which are dependent on rainwater or mist to bring them together. Once united, these cells form a sporophyte, which is a tall slender stalk with a capsule full of spores at the end. When conditions are right, the capsule erupts to broadcast the spores with the wind, forming new plants away from the original colony.

Another unique way that mosses developed to cope with life on dry land is their ability to go dormant during droughts and revive once they receive water, sometimes surviving as long as 19 years without water. Scientists are studying the genetics of this drying without dying in mosses with hopes of helping other crops survive in drought conditions.

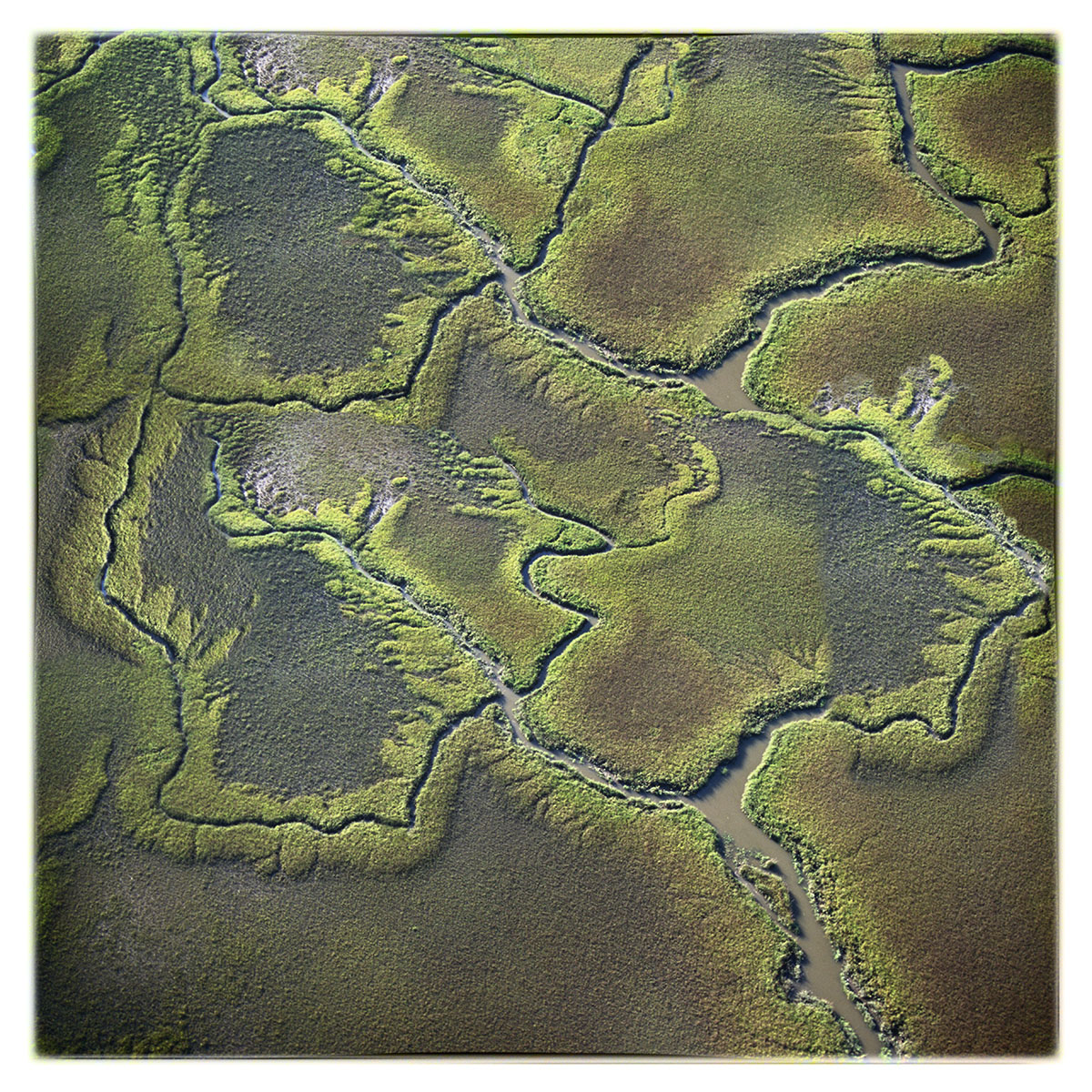

Slime molds

Slime molds are not plants, animals, or fungi, but are brainless, single-celled soil amoebas in the Protista Kingdom. They are one of the oldest lifeforms on earth and are believed to be over one billion years old. Molds are incredibly diverse organisms that can be found in a huge variety of shapes and colors, living in dark moist places such as under logs and leaf litter which they devour and transform into nutrient rich humus soil that plants need for survival.

Slime molds have no feet yet they can join by the thousands and crawl in search of food. Researchers have discovered that molds are remarkably efficient at tracking food and have devised tests by placing molds in a maze and observing how it methodically sends out tendrils and navigates to a food reward at the end. Researchers then removed the mold from the maze, cut off the tendrils and tried the same experiment the following day. The brainless slime mold “remembered” the maze and quickly reached the food reward. Tests such as this with lower lifeforms have led researchers to rethink our narrow definition of consciousness.